Invasive Species & Climate Change

Invasive Species & Climate Change

When you look into the various effects of climate change, there are plenty of passing references to invasive species. When you look deeper, though, you find a mixed story. Before we dive in, let’s look at the definition of “invasive species.” On February 8, 1999, President Clinton signed an executive order that amended a number of preceding orders to define invasive species and describe the federal government’s responsibility in managing them. In essence, an “invasive species” is (1) non-native (or alien) to the ecosystem under consideration, and (2) one whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.

There’s an important distinction to be made between non-native species and invasive species. Not every newcomer to a given location is invasive or detrimental. Whether a species is relocated or “migrates” to a new area, its status as invasive depends on the extent of harm caused by the species in its new location.

An example of a non-native plant species in the Adirondacks is the colorful bigleaf lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus). There is a native lupine in the Adirondacks—the sundial lupine—but this is not the plant commonly seen along roadsides and in yards and fields across the region, into New England, and out west. The sundial lupine (Lupinus perennis) is in decline due to fire suppression, and habitat fragmentation and loss. Its population has declined so much, it is presumed extricated in Maine and listed as critically imperiled in Vermont and vulnerable in New York.

But the decline of sundial lupine is not caused by the introduction of the bigleaf variety, and folks really like the bigleaf variety. According to a 2005 Bangor Daily News article, when Acadia National Park’s botanists attempted to eradicate the plant, a vigorous protest brought the effort to a halt. Their approach now is to remove plants only where they encroach on other sensitive vegetation. Besides being iconic and pretty, bigleaf lupine also offers several benefits. As a member of the legume family, it has nitrogen-fixing properties that help nourish the soil for other plants. They also attract a number of pollinators, and their strong taproots make them good at combatting erosion, as well.

Compare this with purple loosestrife, an invasive non-native species found in wetlands and low-lying areas, such as roadside ditches. It can stand between 3 and 12 feet tall with showy blooms beginning in mid-June. What makes it invasive? First, it spreads very quickly. With a single plant producing in excess of 2,000,000 seeds a year, it can quickly spread and outcompete native species for resources. Once established, the plant creates dense monoculture canopies that prevent other species from germinating and discourages native waterfowl from nesting. The plant’s roots and numerous stems trap sediment, clog waterways, and make water murky. Fish, amphibians, and reptiles like turtles are all negatively impacted when ponds, marshes, and other wetlands are choked with loosestrife, not to mention the potential human and commercial impacts. Purple loosestrife is versatile enough to spread to dryer areas too, like meadows, and can regrow from stem pieces, so you can spread it around by mowing it down.

GETTING HERE

How do non-native species get here?

- Migratory animals. Example: Japanese honeysuckle, whose fruits are eaten by birds, who in turn distribute the seeds as they travel.

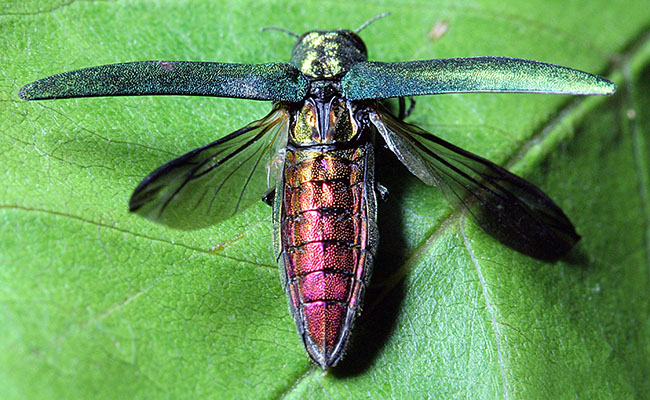

- Human recreation. Example: Emerald ash borer, often moved with firewood.

- Shipping. Example: Zebra mussels, which arrived on ships’ hulls or in tanker ballast.

- Medicinal use. Example: Dandelions, introduced by early settlers. Today they are considered naturalized non-natives, but not invasive.

- Home gardening. Example: Giant hogweed, whose sap causes burns and can cause blindness. It was originally introduced as an ornamental plant.

- Pet ownership. Example: Goldfish, which are a type of carp. Released into the wild, these are a growing menace in waterways all over North America.

- Commercial cultivation. Example: Nutria, a large, South American, semi-aquatic rodent that was originally imported to Louisiana fur farms in the 1930s. Some escaped during hurricanes, others were released when the nutria fur trade bottomed out. Nutrias are now established in seventeen states.

- Biological controls gone wrong. Example: The harlequin ladybird, intentionally introduced to control aphid populations. Larvae of the harlequin ladybird eat the larvae of other ladybird species, and carry parasitic microsporidia that kill susceptible native ladybugs.

All but one of these introduction methods are through human activity.

No matter how they arrive, what all naturalized non-natives have in common is that they are resilient and opportunistic. They are good at adapting to their new surroundings and taking what they need without intervention. When a naturalized non-native has no natural predator or other environmental checks to keep it in balance, it has an opportunity to become problematic.

THE IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Invasive species are a problem. Now let’s factor in the impacts of climate change:

- Native plants, animals, and organisms may spread to new areas as hospitable conditions shift, essentially making them “alien” species to new locations.

- Species that are already naturalized to an area, but aren’t currently invasive, could gain an environmental advantage if they can adapt to weather and temperature changes better than native counterparts.

- New overseas shipping routes made possible by warming waters and changes in traditional ocean currents create new corridors for potential introductions.

- According to a 2018 study by Cornell Lab of Ornithology, changes to the jet stream related to climate change will make it more difficult for birds to migrate south for winter, and easier to fly north in spring, potentially changing bird nesting locations or even population counts of some bird types.

- As habitats shift—as whole biomes shift—the fauna living in them move as well. U.S. National Parks have documented animals making their homes on higher ground to escape excessive heat, for example. National Geographic published an article in 2017 highlighting that as many as half of all species are moving now, toward cooler temperatures, more water, and/or more abundant food sources.

- Infectious diseases will rise as a result of climate change. In fact, they already are. Warming bodies of water encourage bacteria and harmful algae growth that can kill fish, make people sick, and be transmitted by birds and other animals to new places. Floods and hurricanes introduce pathogens into water supplies. Animals that support black-legged and lone star ticks, including deer, wild and domestic dogs, squirrels, birds, and mice, carry the ticks with them to new places. Warmer winter temperatures allow ticks to live farther north than before and stay active in winter months. Illnesses that used to be isolated to smaller regions are being seen in wider locations as conditions allow pathogens to spread.

As with the impact of climate change on alpine plants, we don’t have sufficient data to project which species will be carried by animals as they move to new places, which will be introduced through human activity, or precisely which species will become invasive, either where they are, or where they will be in the future.

The interconnectedness of all the players, as it were, in a given ecosystem or biome means there will be some unexpected outcomes as variables change within that space. In drought, you could predict that migrating animals who rely on vegetation along their route would either migrate more quickly, or go hungry. But who would have thought that drought could actually increase mosquito populations and therefore result in higher transmission of disease? In other words, it’s complicated.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

Erin Trombley is ADK’s former Digital Marketing Coordinator.

Related

Leave No Trace in American Sign Language

As many outdoor organizations look to include more diverse groups of outdoor enthusiasts, Adirondack Mountain […]

Homeschool in the Woods

Homeschool in the Woods is ADK’s newest youth program. It is a place-based, hands-on, and […]

Beavers & Climate Change

Beavers: Furry wetlands residents with buck teeth and a paddle tail. Also, New York State’s […]

Nurturing the Next Generation of Stewards

By Tom Andrews, ADK President The Adirondack Mountain Club has a long history of connecting […]